Creativity makes rare public appearances. People are most likely to report feeling creative when they are in their cars, according to one study. Consider the advantage of a private vehicle over a space shared with hundreds of others.

Cars can:

- Immerse us in a novel, sensory experience whose climate and choice of music we can tailor to our minute-by-minute preferences

- Provide us with a tactile opportunity to move our hands, so our minds can engage in unfocused, meditative reflection

- Constrain our options with clear, rules-based templates, while still allowing for spontaneous improvisation

A car would be an ideal habitat for creativity if people were able to write, collaborate, hold meetings, and drive at the same time.

Public spaces do not typically allow this kind of individual flexibility and personalization. Waiting in queues, wrangling group members, and looking for the departure gate are more likely to induce panic than creativity. A workplace likewise faces its own obstacles—from time and resource constraints to physical constraints to unclear expectations.

Three additional factors inhibit creativity in modern public spaces:

1) Technology and our modern bias for calculative thinking—actions and thoughts that produce measurable results

2) Fear of judgment

3) Homogeny and standardization as spaces must meet diverse needs

1. Technology and Our Bias for Practical Thinking

Business people and educators have long placed a premium on all that is measurable—from domain knowledge to technical skills. If creativity cannot be measured, then it cannot be real. And if it isn’t real, then how can it be worth the time? Innovation and design have emerged as the measurable and therefore valuable forms of creativity, while traditional arts programs like painting, sculpture, and music receive less and less funding each year. Meanwhile, technologies from touchscreens to smartphones to wearables are creating entirely new patterns of human behavior. As humans merge with our machines, we are restructuring our hardwiring.

Scientist Edward O. Wilson refers to this process as “gene-culture coevolution,” which he calls “a complicated, fascinating interaction in which culture is generated and shaped by biological imperatives while biological traits are simultaneously altered by genetic evolution in response to cultural innovation.”

Henry Francis Mallgrave writes, “The key to this gene/ culture reciprocity is certain ‘epigenetic rules’ (changes caused by mechanisms other than changes to the DNA sequence) that ‘direct the assembly of the mind,’ and culture thereby becomes ‘the translation of the epigenetic rules into mass patterns of mental activity and behavior.” [2] Technology is structuring our days— and our brains—so that we are becoming conditioned to look to screens and devices to provide instant feedback and communication, deprioritizing any activity that does not provide feedback or lead to a measurable outcome. Mallgrave writes that our own neural plasticity makes us “more susceptible to the influences of technologies and culture than we formerly believed,” and that “plasticity can work both ways. It can enhance or delimit our perceptual or cognitive processes, and at a much faster pace than genetic theory allows.” [3] When every task is calculated to produce a rapid result, it is easy to forget why any of these tasks matter. Mallgrave cites artist Warren Neich, who refers to the process of sculpting the brain as “visual and cognitive ergonomics,” explaining that “when neural networks are activated over and over again by similar stimuli they form ‘amplified maps’ for these stimuli, which not only operate faster and more efficiently but also acquire a neurological advantage over other networks.” [4]

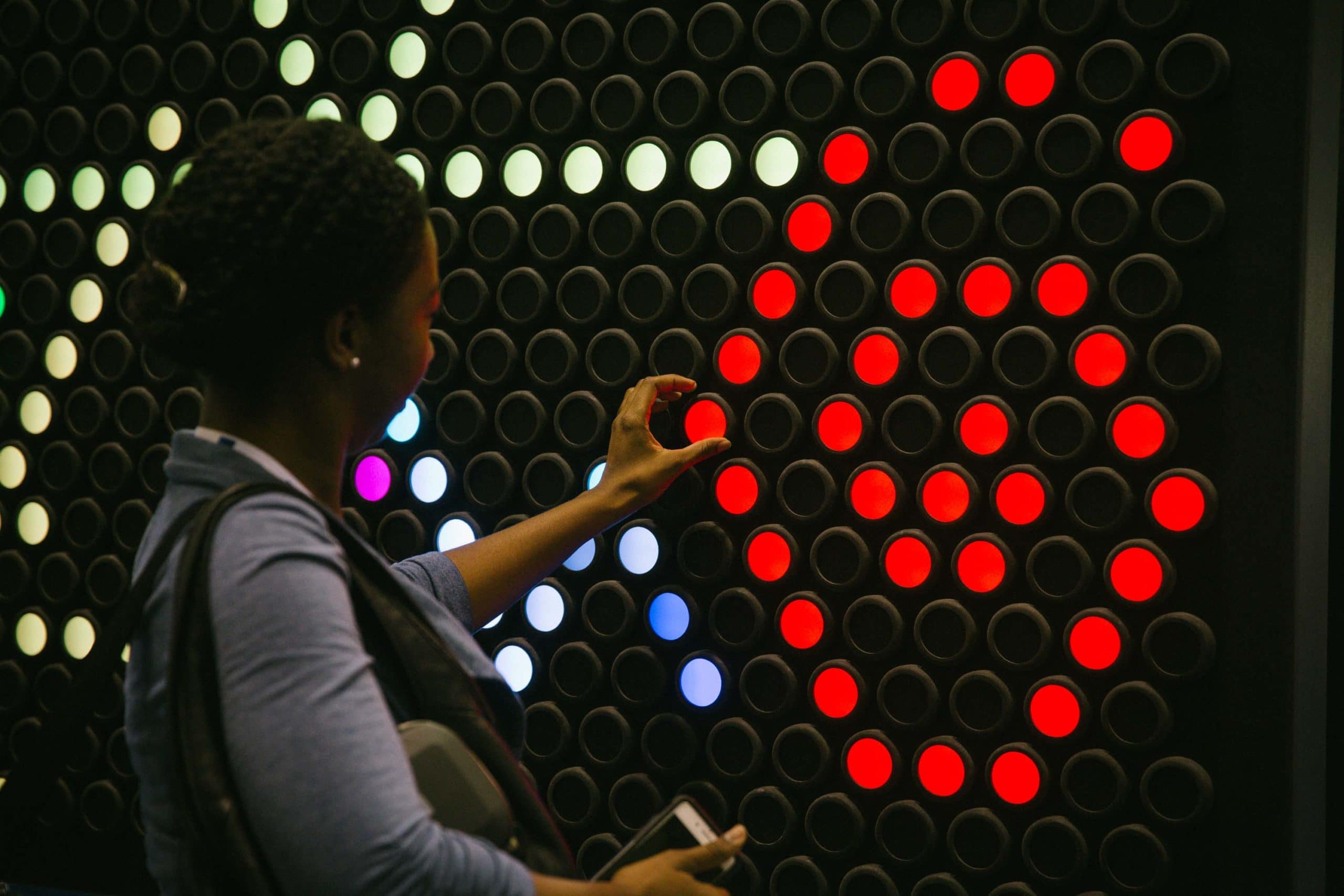

Professor and writer Diane J. Bowser puts a sharper point on it, arguing that our technologies have engaged us in a “game of trivial pursuits where we do nothing but interact for the sake of communication itself.” [5] Coupled with this monopoly of measurability is a technology-driven reliance on one human sense—vision— above all others. New spaces and buildings are designed to appeal primarily to the human sense of vision by inspiring feelings of calm and wellbeing. Although awareness of the body-mind connection and differences in work styles have led many organizations to embrace sensory features like standing desks and introvert phone booths, these serve a measurable organizational purpose such as higher productivity and employee engagement. Tactile, creative play—which engages all of the senses and activates the part of the mind responsible for high-level executive decisions—is not typically sought after, because it is not perceived to be linked to measurable outcomes.

2. Creativity In a Public Space Feels Risky

Whether it’s fear of judgment or fear of being interrupted, simply being in a public space adds a highly risky and unpleasant element to creativity. Most people do not want to paint on giant canvases in public. We can’t all be accomplished artists. The fear of judgment is imminent, not to mention the mess. When given a choice between delivering an impromptu toast at a wedding reception, and giving directions, many people would prefer the latter. The conditions for an idyllic, secluded creative environment, free of social shame and interruptions, would be very difficult to replicate in a public space.

3. Public Spaces Are Designed for Groups, Not Individuals

All organizations want to attract highly-motivated individuals. Humans need to be creative on a daily basis, and high performers are no exception. However, creativity is not just personal and individual. It is domain-based and cultural. The degree to which people are encouraged to produce and submit new ideas, and the speed at which they are accepted and incorporated, are highly specific to one’s domain. In some industries, new ideas take years to gain adoption. This presents challenges for large organizations in more traditional, conservative fields. It can be frustrating for innovation-minded individuals who want to feel like they are making an impact.

For a company, this could result in a difficulty in attracting and retaining top talent, who want to be given the opportunity to create work that makes a difference. For a community (such as a library or a hospital), this discouragement results in low engagement, in people not wanting to visit, not wanting to linger, not feeling at ease or safe, and being easily distracted by other competing activities, such as video games, social media, TV, gossip blogs, and fragmented surfing of the internet. Additionally, people need different amounts of collaboration and independence. They need the flexibility to dial in their individual needs for privacy, without compromising a neighbor’s need for collaboration. Fortunately, emerging solutions in tactile creativity are striking a balance between diverse needs to overcome many of these obstacles.